If growing a startup wasn’t hard enough already, consider this scenario:

Google hires a smart MIT Masters graduate to a seven year contract. She’s enrolled in a mentoring program and handed a couple of key projects in London to prove her mettle. Larry Page nurtures her career. She’s stellar after 24 months; a superstar after 48. Five years after graduation, she’s ready to join a startup in Austin as founding CTO. Google is reluctant to let her go, but finally accepts a $2M transfer fee, plus 15% of any royalties arising from any patents on any inventions she creates for the next five years. The startup agrees to pay the fee in three installments over the next 18 months.

Welcome to employment and recruiting if the labor market worked the same way it does in professional soccer (aka football for everyone outside North America). You probably think this scenario completely weird but if startups recruited like Premier League Clubs, talent acquisition would be much different:

- Would it reduce the number of recruiters camped outside campuses of Google and Facebook trying to catch the eye of in-demand talent?

- Would the top 1% of performers in any given field, so-called Rockstars, whether developers or product wranglers, benefit?

- Would it affect the way startups grow or the economics of transforming an idea into an exit?

Football: Where Players Are Well Paid But Their Movements Restricted

Football is the world’s most popular sport. It’s played everywhere and enthralls hundreds of millions of fans every week. Virtually every country has some kind of professional or semi-pro league, providing a living to tens of thousands of players. Most of these them, including everyone at the top levels, live in a world where restriction of movement governs their lives from the moment they sign a professional contract.

The concept of labor, the people running around on the field, in the world of football is very different from the concept of labor for you and me. In most countries, you’re free to move from one job to another. In California, for example, the norm is an “at will” employer-employee relationship. Either side can terminate it on any day for any reason (as long as the reason is legal). Professional footballers don’t have this option. They’re tied to the club that owns their contract until it runs out, is replaced by a new one, or the buyout clause is triggered by a club offering a minimum bid. (Lionel Messi’s clause is $250M euros). The only time players are completely free to negotiate with anyone is if they’re released, which means their contract has ended. Until then, they’re highly compensated property of their clubs. In reality, there are multiple ways to force a transfer move. The acceptance, however, that clubs can control players as assets and be rewarded for asset appreciation is almost unknown in other sports and industries. It’s fascinating.

The Transfer Window

The catalyst for this post was the recent end to the transfer window. According to the governing body of soccer, transfers are limited to winter and summer windows; July 1-Aug. 31 and Jan. 1-31. (Here’s a detailed explanation) During these periods, clubs acquire and dispose of players. The basic process is:

“Club 1 has a player. Club 2 wants a player. Club 2 and Club 1 thrash out an agreeable price, the player and Club 2 thrash out some agreeable wages, and then the transfer happens — the player’s registration is transferred from Club 1 to Club 2, and he signs a new contract — and all parties are happy.”

At the top levels, domestic leagues in Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the England, individual transfer amounts routinely exceed $3M. In case you were wondering, the aggregate is a big number; English clubs spent almost $1bn (£652m) in the just-closed window on approximately 360 players.

Applying Football-Centric Employment Principles to Recruiting

Let’s keep the same employment model but switch industries. How would restriction of movement change the way Silicon Valley startups recruit and employees search for new opportunities?

1. Most people would still have to actively find a new job

Most people have to look for jobs. If you’re good enough, job opportunities will find you. Recruiters come knocking. You’d be able to take advantage of them because your new prospective employer, that hot Internet of Things startup, would be willing to spend some of its VC money on your transfer fee.

2. Transfer fees would be low for the vast majority

This really isn’t much different than in football. There are only so many exceptional football talents. Similarly, there are few employees who can materially impact the futures of companies by themselves. Most employees are part of a team and plotted somewhere in the bulge of a bell curve. They’re unremarkable and replaceable. You may be a solid employee but without a personal connection at the new company or someone there ready to vouch for your abilities, you’ll struggle to stand out in the crowd and the transfer fee will be low. You may shine later but when you’re at the door, waiting to prove yourself, the number isn’t going to be huge. (This isn’t bad for the new company; it is for you if the fee will be shared). If you have teased the world with your potential (remember that 17-year-old Brit who sold his news app to Yahoo! for $30M?), the transfer number is going to be huge.

3. Name brand multiplier

This isn’t much change from the status quo. People who’ve spent time at successful companies, especially during the company’s ascent, reap the benefits of perceived competence or brilliance. If you’re in Google’s mapping department, offers will find you. Whether Google agrees to let you go……well, you’d have to wait.

4. Talent would concentrate

While top players often secure exits on their terms to their new club of choice, the biggest names in football, the Man Cities and Uniteds, are big enough to just ignore requests. (See Carlos Tevez’s last 18 months at City). The richest companies like Apple, Google, Intel, Amazon and Toyota could just do the same. If you’re big enough and wanted to prevent other aspirational up-and-comers from getting ideas, you could just play hardball.

5. Top talent would get rewarded

In every field, the best bankable talent gets the biggest share of the pie. Our two scenarios don’t change the outcomes much for elite Silicon Valley engineering talent. In both cases, the 5-percenters will be handsomely rewarded. The difference, as illustrated in our opening scenario, is that the current employer will be rewarded with a transfer fee now and some kind of follow-on if the Rockstar really stars at the new gig. Either way, the engineer is going to make a lot of money from salary, benefits and future equity.

6. Employment contracts would become shorter

Employees, especially those with confidence and skills, would pursue shorter contracts. If you know you’re good and know that your value will rise in three years, you’re probably not going to be interested in a five year-deal unless you need the comfort of a dependable future.

Talent Acquisition Gets Harder for Startups

Startups would probably find it harder to hire the elite. At least everyone but the truly well-funded. You couldn’t just offer 10% of an amazing opportunity to a top talent and expect him to start in 2-3 weeks.

Selling companies might just refuse to part with their talent. The lure of non-diluted equity and building something from scratch, which attracts so many early employees probably wouldn’t be enough in strict monetary terms. Buyers might have to be creative. One alternative might be that companies would be willing to let talent depart in return for transfer fees in the form of equity. The result is you get the talent you need but accelerate your dilution. Your cap table could become pretty messy pretty quickly. (It could lead to some interesting Business Development and Partnership discussions, though).

Recruiting would probably change, too. Your top talent would be less likely to jump but if they did, replacing them could be much more challenging. You’d have transfer money to use to acquire replacement talent, but you might be unable to land your top choices.

Talent Acquisition in the Spotlight

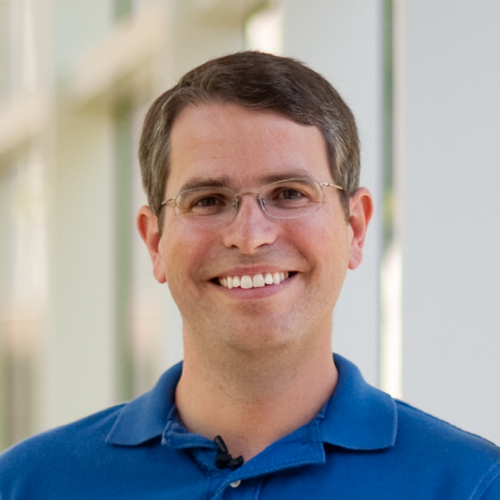

The football transfer market captivates hundreds of millions of football fans each year. An employment market wouldn’t generate the same hype because the fortunes of companies change at a much slower pace. Some job categories, though, would be slavishly followed and analyzed. Just imagine the enthusiasm, despair and jealousy that would erupt on Quora, Reddit and other specialized communities. The online marketing community, in particular, would go without sleep if SEO uber/mega guru Matt Cutts announced an intention to leave Google. I’m sure a startup somewhere would offer Google $5M. Would Google accept it? If startups recruited like football clubs, we’d quickly know.